What challenges do we encounter when translating journalistic texts – which of these are text-specific, and which crop up repeatedly, just in different garb. Henriette Reisner on topics discussed in our Neustart workshop.

What challenges do we encounter when translating journalistic texts – which of these are text-specific, and which crop up repeatedly, just in different garb. Henriette Reisner on topics discussed in our Neustart workshop.

As the British writer Anthony Burgess so aptly put it: “Translation is not a matter of words only: it is a matter of making intelligible a whole culture.” dekoder has been regularly translating Russian texts into German in pursuit of this mission for several years. In 2019, it began translating German texts into Russian as well, and in 2020, Belarusian texts into German. But what happens when journalistic texts are translated into a different language, when a whole media landscape is translated into another? And what do translators have to bear in mind when tackling this complex task? This report presents some of the challenges encountered and experiences gained during translation work at dekoder, along with some questions that the translator of a journalistic text does not necessarily have to answer, but should definitely keep in mind.

Making a culture intelligible through the lens of a media landscape

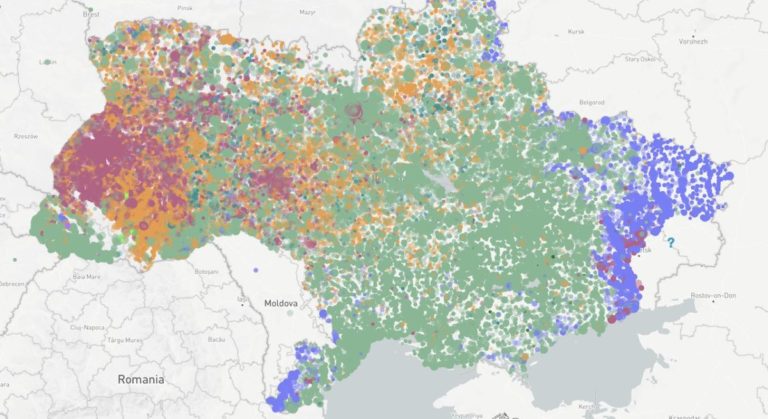

In line with the quotation above, together with Burgess we can assume that translation is not limited to the level of language alone. Rather, it involves the attempt to make “a whole culture” intelligible – and in dekoder’s case, to do so through the lens of a media landscape, or rather a specific niche within that landscape: the “independent” media in Russia. At dekoder, the editors are responsible for informing readers how the individual media and authors fit within the larger context. But what do the translators need to consider when translating articles? Journalistic texts tend to have a strong cultural dimension because they often contain idioms, wordplay, metaphors, allusions, and so on. In journalistic texts in particular, translators have to ask themselves: Where does a text require, through implication rather than explicit communication, cultural knowledge? That is, knowledge that dekoder’s readers, who are reading media that originated in another cultural environment, cannot be expected to possess?

One proven means of conveying background information that dekoder uses regularly is what we call the “blurb”: a lexical or explanatory note that appears in a small text window and provides a brief explanation. Through these blurbs, a term for instance, may be unobtrusively explained. Sometimes a blurb will be linked to a more detailed text written by an expert. At dekoder, this more comprehensive format is called a“Gnose” (from the ancient Greek “gnosis” – knowledge). This, from the translators’ perspective, is an elegant approach, as it frees them to adhere as closely as possible to the original text – and it is a clear advantage associated with an online medium.

At dekoder, blurbs fill in the missing context

There are intra-textual options for addressing gaps in context as well, such as small insertions providing the missing information or small omissions to remove references that would be irrelevant or potentially confusing to the new target readership.

But how are political metaphors and concepts transferred from one language and cultural environment into another? Terms, concepts and institutions can have differing connotations, and the ideas bound up with them were shaped by different histories. To illustrate, a simple example: the meanings and ideas we associate with the words (political) “left” and “right” vary a great deal depending on the cultural environment and political tradition in which we grew up. As long as we remain within our own frame of reference, our own coordinate system, we rarely have cause to think about what we mean by these terms; the translator, though, must be constantly aware of the possibility of differing conceptual associations and, in some cases, find a finely tuned solution that does justice to both conceptual worlds.

Dealing with metaphors and stylistically marked language

Another challenge: a form of expression that constitutes completely neutral usage in one language (and would not cause the slightest discomfort to readers of that language) can come across very differently in another language, as insensitive or discriminatory, for instance. In other words, sometimes ways of expressing things that are unmarked in the source language are marked in the target language (the reverse is also possible, of course). In any case, the translation of a journalistic text should both convey the same informational content and produce the right effect (equivalent effect). This latter point suggests that the translator should, if possible, avoid irritating the reader through the use of terms that are marked (only) in the target language, as this would alter the effect and perhaps even distract from the information the text is intended to convey. Experience suggests, however, that the target language can tolerate more “foreignness” than we tend to suppose, meaning that here, again, the translator needs to weigh such cases delicately, in order to fulfil both requirements (equivalence of effect and content) as well as possible.

Journalistic traditions and degrees of emotionality

Those who translate journalistic texts also need to be aware that journalistic traditions often differ greatly and that, along with them, individual journalistic genres and reading habits can also differ significantly. This poses a challenge for the translator, who must figure out how to adapt the text to accommodate those differences. In this respect, it is certainly advantageous to have a general grasp of the characteristics of journalistic texts and of the specific features of the various journalistic genres, including those particular to the different media cultures, so that you can take these into account when translating into German (or another target language). And there are other, more general questions that it is helpful to keep in mind. For instance, what language devices are used in the original text and what characterises its style? What is its intention, its speech attitude? What readership is it aimed at?

Another important question is how to deal with different degrees of emotionality and the means used to impart expressivity in a text. In this respect too, languages can vary considerably, and translators need to take these differences into account. When it comes to arranging the informational content so as to be as transparent as possible in the target language, syntax plays an important role: syntax is largely responsible for ensuring that the appropriate weight is given to each individual word or element in a sentence, and that each piece of information is accorded the appropriate degree of emphasis. A case in point: important information is often found at the end in German and English sentences, but in Russian, such information is usually found in the first or second position in the sentence. “Wer zuletzt lacht, lacht am besten” (word for word: who as-the-last laughs, laughs best); “he who laughs last, laughs longest”; and “Khorosho smeetsia tot, kto smeetsia poslednim” (word for word: well laughs the-one who laughs last).

Ending with the trickiest: The joke

If one were looking for journalistic translation’s equivalent to the solo dance in competitive figure skating, one might look to the translation of a meme, which demands individual creativity and involves challenges relating to nearly all the requirements of journalistic translation. To translate a meme is to transfer or even catapult a phenomenon specific to one culture and the joke deriving from it into a different linguistic and cultural environment. That, it turns out, is not always easy. This is partly due to the added complications that arise when the meme format is more widespread in one language environment and enjoys a different status among the original- and target-language readerships. Nonetheless, it is often possible to come up with creative solutions that account for both the meme’s use of language (from simplified language to incorrect grammar) and its visual components.

Finally, the same principles that apply to any journalistic text (in its original language) also apply to journalistic translations: they should be accurate and transparent, at once dynamic and easy to read. In applying these principles, the translator should respect the author’s style and the intention, while never losing sight of the new target readership.

We can succeed at this balancing act if we recognize that each text we translate will test the boundaries of our own linguistic coordinate system, which shapes our perceptions of the world. However, this testing leads us not only to barriers, but also to unexpected possibilities for stretching our own language and its robustness as a vehicle for meaning.