Journalistic texts change over time and with the setting, manner and context in which they appear. Novaya Gazeta’s reportage is an example. How is this manifest during translation? Irina Bondas sets out on a path through texts, times and languages.

We stayed in Chechnya for two weeks and were able to move around freely and meet with whomever we wished, although in the end we were unable to get an interview with Kadyrov. I then did some interviews in various European cities and in Moscow. At that point, I wrote a first draft of this reportage, which took a broadly optimistic view. This view was called into serious question by the murder of the Memorial activist Natalia Estemirova on 15 July and a series of other murders shortly thereafter. I have therefore completely rewritten this text to take these events into account, finishing it in October of 2009. I am publishing it in this form, aware that still more recent events will already have rendered parts of it obsolete.

Jonathan Littell, Tschétchénie, An III

WITHOUT THE DESIRE TO READ, WE WOULD HAVE NO NEED TO TRANSLATE

Jonathan Littell prefaces his 2009 Chechnyan reportage with this disclaimer, thus laying his cards on the table: this text is out-of-date. All the more so the German translation, which was published later that year; and between then and now, when I hold the book in my hands, more than ten years have passed. So why read it? Perhaps you are rolling your eyes, as I myself may be. The question may well seem a bit contrived, yet it demands an answer. Because, or so my thesis: without the desire to read, we would have no need to translate. If I read to keep up with the current of the times, to have something to contribute to the discussion, I am certainly not doing justice to literary texts – and not, for that matter, to journalistic texts either. What is more: I am not even doing justice to the current of the times.

Tschétchénie, An III is a record of a particular place and time, rendered a literary work through its book form, and no longer anchored in time. By reading it, one can turn back time, transport the distant into the now. Journalistic texts can acquire this power, can still say something new, long after they have been overtaken by events and ceased to be news.

Every time I read one of the excellent reportages or investigative pieces by Novaya Gazeta reporters Anna Politkovskaya, Pavel Kanygin or Elena Kostyuchenko, I feel like I have understood something important, both about Russia and about life itself. Something that reaches far beyond the topic at hand.

NOVAYA GAZETA REPORTAGES – A FORMATIVE GENRE

In February 2022, when the writer Sergei Lebedev was asked at a reading in Basel’s Literaturhaus what book best explained today’s Russia, he named Anna Politkovskaya’s books. I have tried and failed to describe how great an impact Politkovskaya’s reportages have had, how much they inspired the next generation of journalists, or indeed how powerfully they influence anyone who comes into contact with them. The reading itself becomes an experience. It is a reading against the current of time, a taking of oneself out of time, and of entering into another time – of stopping the flow of time and, at the same time, of capturing it.

ABOVE ALL, THERE IS A GREAT DEAL OF TIME THAT IS NOT TOLD

When translating, one is always looking to gain time. Time, in fact, is the currency of our world: there is the time that is actually being told and the time of the telling, which is limited by the number of keystrokes, but above all, there is a great deal of time that is not told. This includes the writing time, the not-writing time, and the re-writing time. It includes the translating time, the editing time and the copy-editing and proofing time. In the worst of cases, the accumulated days, weeks and years will translate into a few minutes of skim reading.

IN THE WORST OF CASES, THE ACCUMULATED DAYS, WEEKS AND YEARS WILL TRANSLATE INTO A FEW MINUTES OF SKIM READING

I imagine that, as a translator, one learns to translate through the years of experience. When I first started university, I believed myself to know much more than I do now. Learning to become aware of problems is the first difficult lesson. Then it’s back to square one. To me, it seems important not to stay in one place if you still want to go further. At any rate, through practice and reflection, I find solutions for problems whose existence I once had no inkling of. Answers can be found in scholarly works on translation. Answers can be found in workshops, in professional development offerings, in conversations with colleagues.

HOW CAN REPORTING FUNCTION UNDER HYBRID CONDITIONS OF BREATHLESS VIOLENCE?

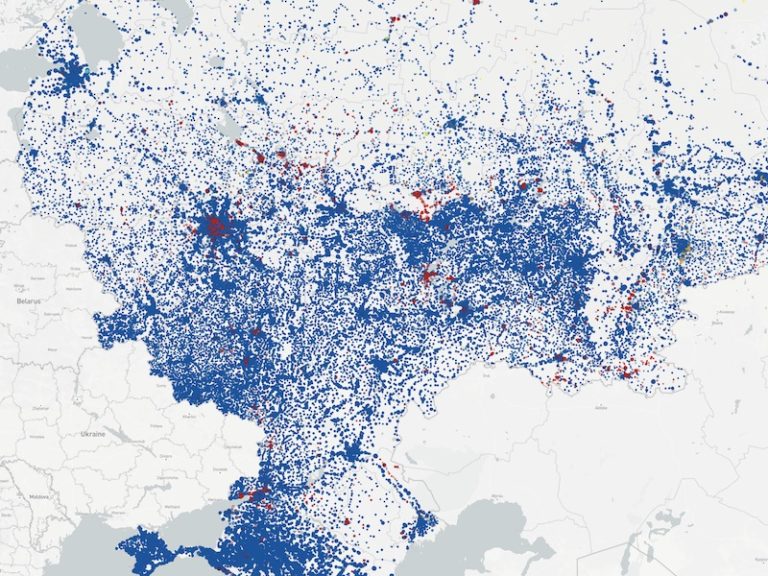

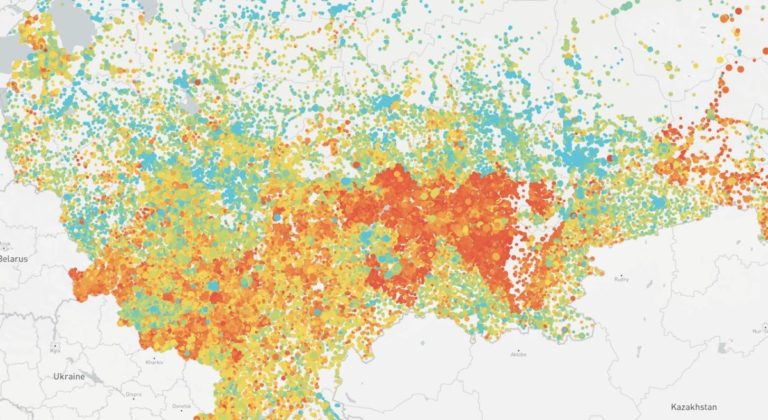

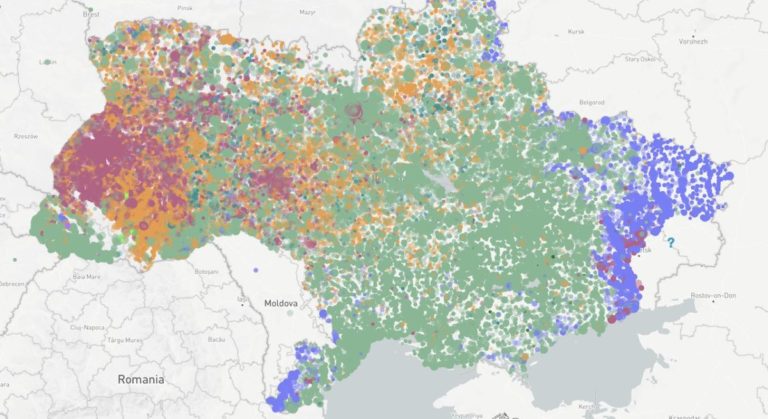

When I first met its current editor-in-chief Tamina Kutscher in connection with n-ost’s journalistic project STEREOSCOPE UKRAINE in 2014, dekoder did not yet exist. Back then, the great need for such a media source was made plain by the public handling of and the media’s bafflement over the chain reaction triggered by the protests across Ukraine which followed the failed association agreement with the EU. These protests have brought and are still bringing, at a breathless pace, violence, annexation and war. In an unprecedented manner, the events of that time had driven a fissure straight through the societies of Ukraine and Russia and beyond, slicing through political camps, occupational groups and families. There appeared to not only be a lack of political statements, but also of experts and negotiating room, and above all a lack of expertise on how reporting could function under these hybrid circumstances.

Many of the reporters participating were from Russia or Ukraine, and I remember watching one evening as specialists clashed over a familiar issue: one side insisting that the time-honoured “na Ukraine“ (literally, “on Ukraine”) was the grammatically correct form, the other calling for replacing “na” with “v” (meaning “in”), which is the preposition normally used for states and countries, rooms and spaces. This latter group argued that “v Ukraine” expressed the sovereignty of the country’s statehood, rather than denying its independence by treating it like a territory (or an island), which, they said, “na Ukraine” did. The usage with “v” has since become common among those critical of the Russian aggression against Ukraine. It was an argument much like one might hear today in German-speaking countries about gender-sensitive language. However, the duality of the Russian terms was already increasingly manifesting itself as an element that shapes everyday reality, in the sense of the distortions that create facts described by Victor Klemperer.

LANGUAGE AS AN ELEMENT THAT SHAPES REALITY

The categorisation of texts on the basis of small markers, word choice and thought structures is a necessary part of the successful translation process – one that has become a heuristic of its own in recent years. When a woman in Berlin asked me for directions to the bus station on the 72nd day of the war, explaining that she and her family wanted to return to Ukraine, I got a sense of which kind of media she consumed: she had said that she wanted to go “na Ukrainu”.

STEPPING OUTSIDE OF THE UNCONSCIOUS

Another bitter pill I had to swallow during my student years was the realisation that my own intellectual affinity with a source text and the intuitive understanding that I – as a “pseudo-native speaker” – had for the world in which it originated did not come close to carrying over into German. “Pseudo-native speakers”, that is what they called us at university, us being the multilingual people who, it was assumed, had not properly mastered any language. That to bring a text closer to the reader, one must often first deliberately step away from it.

At the same time, though, the key to the meaning of a text is in its tone, its temperature. Neutrality in language is a lie of necessity that theory tells. But experience with nothing to ground it is of no use for the communication of meaning – far from it. I believe that for bodily knowledge to become a useful resource, a translator must first develop an awareness of it and train it into a skill. Knowledge that cannot be consciously applied, controlled and reflected upon will obstruct the view of the original with memorabilia of its own. Swayed and swathed by my own past and biography, I must first fight my way clear, achieve a conscientious stance – which is to say one characterised by both carefulness and a moral compass.

As a translator, I need to be mindful of the not-translating, that which resonates with the written, namely the unwritten, and hence that which is augmented by the readers, which comes into being during the reading. “What is meant is always more than what is said,” Prof. Larisa Schippel says in the podcast Überübersetzen. Based on my work as a conference interpreter and translator, I would modify that sentence: the unsaid is always more than the said. The unsaid is the untranslated. The untranslated is not untranslatable, because anything can be translated in many different ways. The untranslated is that which contributes to constituting a translation without being a part of it. It is the time that passes (during and in and prior to the translation), the sentences that are deleted, the genesis of the mistakes. Every translation has multiple sub-, con- and non-texts. The translation is the vehicle for a multiplicity of translated information which does not have to be translated. And which is nonetheless the very stuff of the translation.

THE UNSAID AND THE UNTRANSLATED

In the case of dekoder’s journalistic texts, there are numerous factors that multiply the unsaid: the Russian texts are produced on a tight schedule, on the basis of events as they unfold, and they are geared toward an audience that possesses certain specific knowledge about the world. They are created within a closed reference system, and their reception takes place within that same system. The translation lifts these texts up out of their native territory, lending functional texts a literary quality: an openness with respect to readership and kinds of reading. The original primary function, the provision of information to a target group in Russia, may soon slip away. Then again, though, the texts gain in meaning through the transfer to dekoder, all the more so as they are contextualised through the addition of background information and explanatory notes.

And then even contexts get new contexts. Founded in 1993, Novaya Gazeta was one of the first independent newspapers based in Russia. By 2021, when its editor-in-chief since 1995 Dmitry Muratov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, it was one of the last. In the epigraph to his essay “On writing”, Ryszard Kapuściński described the final words in the diary of polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott as “the most dramatic definition of reportage” he knew: “Those rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale.” This definition can be taken literally in the case of editors and reporters of Novaya Gazeta: Igor Domnikov, Yuri Shchekochikhin, Anna Politkovskaya, Anastasia Baburova and Natalia Estemirova were all murdered, and many of the paper’s other employees have been arrested, tortured, injured and driven into exile. Their work tells us about Russia and its population. The context makes their bodies the wider context.

TO WHAT EXTENT IS THE SIGNIFICANCE OF A GOOD REPORTAGE TRANSLATABLE?

I wanted to pursue the question of the extent to which it is possible to translate the significance of a good reportage that can, within its sphere of influence, come as a revelation and yet at the same time be fatal. I have fallen short of the mark, though, I cannot write the courage of people who are willing to sacrifice their lives for the work they believe in. I have not succeeded in delineating for the readers what constitutes the specific significance of the Novaya Gazeta reportages for the society in Russia, surrounded by the lies of the state propaganda, camouflaged as news, or the significance they hold for us, through the insight they offer into mechanisms of contempt for humankind that have made the impermissible, the unthinkable, possible.

THE INTUITION OF THE TRANSLATOR AT WORK: A SPECIAL KIND OF EMPATHY

I have written and erased, written and erased. Over the course of months. These months remain, in all their untranslatability, unwritten in this text. I suspect that it is in this, in the unwritten, the out-of-date and in the rapidity with which texts become out-of-date that it becomes palpable to us. I think that this too belongs to the intuition of those who translate: the anticipation of bodily knowledge. We’ll call it a special kind of co-sense. It is not easy and it certainly does not pass by without leaving a trace, even when these traces can now only be found in what has been erased – or what has been eradicated. Neither my research nor the time that has passed can be found in this text. The time since the war-time experiences of past generations of my family, to the collapse of the Soviet Union, to our emigration to Germany, my student years, all the way up to the present, suddenly crushed in on itself, like a piece of sheet metal in a motorway pile-up.

Novaya Gazeta does not exist anymore. The places and cities, the protagonists and authors of those reportages do not exist anymore either. The reportages exist, though. And the translations exist. Just as the apricot trees exist in Inger Christensen’s Alphabet. And the atomic bombs. And, perhaps, those who read exist. Those who read the translations exist, perhaps, will still exist even if someday there is no longer a single reader left for the original.

Thus, in my wishful thinking, the circle closes, I return to my starting point, like the hand on a clockface: the translations will have caught and collected the past, the time lost and undisclosed, like a rain barrel collects water.

For what purpose? I have no answer to that right now.